Ará Ọ̀run kìn-ìn-kin-in:

“There are no people without traditions and traditions are the lifeblood of a people. A people who refuse to express its love and appreciation for its ancestors will die because in traditions, if you are not expressing your own, you are participating in and expressing faith in some else’s ancestors. No person is devoid of an attachment to some cultural foundation. Whose water are we drinking?“… Molefi K. Asante

In the ever-changing world of the Yoruba people of southwestern Nigeria, Benin Republic,Togo,Brazil and Venezuela, one thing that remains consistent is a close connection with their ancestors. The ancestral spirits of the Yoruba are much more than just dead relatives, they play an active role in the daily life of the living. They are sought out for protection and guidance, and are believed to possess the ability to punish those who have forgotten their familial ties. While there are numerous ways the ancestors communicate with the living, one of the most unique is their manifestation on earth in the form of masked spirits known as Egungun.

While Yoruba women and men taking part in Egungun rituals, they now play an active role in some of the Egungun festivals. .

In order to better understand the importance of the Egungun to the Yoruba, it is helpful to know a bit about the their concept of life after death. They believe the transition from the realm of the living to the abode of the dead is not finite, as many other cultures do. It is just part of what African author Wole Soyinka describes as the “cyclical reality” of the “Yoruba world-view” .

Each person comes to this life, from the world of the unborn, through the “abyss of transition.” And each will leave again through this archetypal realm, as they make they way to the world of the ancestors. When a child comes into this world, he or she is said to carry with them aspects of a former ancestor who is reborn in the child. This is to say they are the ancestor reincarnate, but that there are certain features of their personality, parts of their physical make-up, and elements of inborn knowledge that come from a previous relative. When the time comes to leave this earth, it is not the end of their existence either. Yoruba scholar Bòlaji Idowu explains: “Death is not the end of life. It is only a means whereby the present earthly existence is changed for another. After death, therefore, man passes into a ‘life beyond’ which is called Èhìn-Ìwà–‘After-Life’”.

The experience in the After-Life for the Yoruba is said to be based primarily on a person’s conduct here on this planet. A few think that when a person dies they return to a new life back on earth in another far away location, yet most Yoruba believe they go on to a place known as Òrun, which “in a general sense […] means ‘Heaven’, or ‘Paradise’, where Olódùmarè (God) and the òrìsà (the divinities) dwell” (Idowu 211). For those who have been meritorious in this life, the After-Life is a pleasant representation of life here on this planet “minus all the earthly sorrows and toils”

The biggest benefit for those who have led a good life is the chance to be remembered by the living. To be remembered is to be kept alive; to remain within the Sasa period, which is the realm of the living, the unborn and the ancestors. Once an ancestor has been forgotten, they simply slip into the vast expanse of the Zamani, where the gods, divinities and spirits dwell. As long as an ancestor remains within the Sasa period, they have the ability to help those here on earth, because “the living-dead are bilingual: they speak the language of men, with whom they lived until ‘recently’; and they speak the language of the spirits and of God, to Whom they are drawing nearer ontologically” (Mbiti 108). In exchange for being ritually remembered, the living-dead watch over the family and can be contacted for advice and guidance.

There are a variety of ways for the living to keep in touch with the ancestors. “The Yorùbá believe that the deceased can be seen in dreams or trances, and that they can impart information or explanation, or give instructions, on any matters about which the family is in a serious predicament. They can also send messages through other persons or through certain cults” (Idowu 206). S.O. Babayemi, a Yoruba drummer and scholar, explains that the spirits of the ancestors, who “ensure the wellbeing, prosperity, and productivity of the whole community,” can be “invoked collectively and individually in time of need. The place of call is usually either on the graves of the ancestors, Ojú Oróri, the family shrine Ilé ‘run, or the community grove Igbàlé” (1). They can also visit in the physically manifest form of the Egungun.

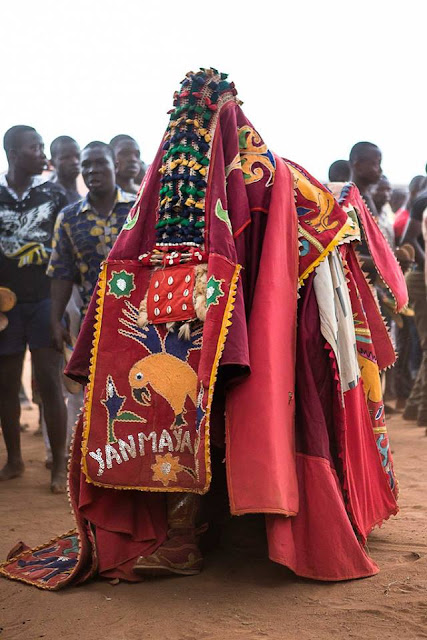

The Egungun are masked men who represent the spirits of the living-dead. Some say they derive their name from the Yoruba word for “bones” or “skeleton,” yet according to Babayemi, the correct pronunciation of the word in Yoruba means “masquerade.” The Egungun appears as “a robed figure which is designed specially to give the impression that the deceased is making a temporary reappearance on earth” (Idowu 208). This impression is enhanced by the complete coverage of the individual. “It is absolutely essential that not a single particle of the human form should be visible; for, if this rule is broken, the man wearing the dress must die (presumably as an imposter!), and every woman present must likewise die” (Farrow 76). Having any contact whatsoever with an Egungun can prove deadly for both the Egungun and the other person, so a whip is often carried to drive people away. “Should he do so ever so slightly (e.g. if the wind caused his garment to barely touch the garment of any ordinary man, woman or child) he would be put to death, together with the person (man or woman) whom he touched, or by whom he was touched, and so also would every woman present” (77). While these policies have changed since British colonization, there is still great respect for the mysterious Egungun.

The costumes of the Egungun vary greatly from region to region. Some Egungun cover themselves in raffia, while others are concealed under an elaborate costume of cloth. The masks they wear may be carved of wood, made of contemporary materials, or composed of such found objects as antlers, skulls or even modern gas masks. In some regions it is popular to cover the face with cloth instead of a mask. This is often combined with a long train of fabric that trails behind the Egungun; the longer and more elaborate the train, the wealthier the family. To complete the illusion, the Egungun must also disguise his voice, which is often disguised in a low rumble or high falsetto.

There are numerous Yoruba myths that explain the origins of these masked spirits. One such myth says that when a man dies his spirit joins the ancestors to become an Egungun. When the body is covered from head to toe for burial, so is the Egungun in heaven, which is why they appear completely covered when they appear on this plane.

Another origin myth tells the story of a king who was not properly buried when he died. “His three sons had no money for a proper burial. The first son saw his father’s corpse and fled. The second dressed the corpse up only to leave it behind. The third, after trying to sell the body in the market (for medicines), finally abandoned it in the bush” (Drewal 91). Many years later when the eldest son had become king, his wife could not have any children. They each consulted a diviner and came to the same conclusion, that he was being punished for his father’s incomplete burial. But his father’s remains no longer existed. To add to his trouble, his wife was then raped by a gorilla, and she ran away pregnant and ashamed. She gave birth to a child that was part monkey and part human and abandoned him in the bush. She eventually returned and told the king her story. He went to consult a diviner who revealed that the child did not in fact die in the bush and that it “would grow up to be Amu’ludun (literally, ‘One-Who-Brings-Sweetness’ to the community).” The diviner advised the king to return to the place of his father’s unfinished burial and perform the proper rites, where his father would “materialize in a costume” (Drewal 92). These are but a few of the many stories that explain the origins of the Egungun.

Each Egungun may represent a particular person, a family lineage, or a broader concept of the ancestors. When contacted at a family shrine, the Egungun who appears is generally thought to represent the ancestor who is being summoned. In the past, such an Egungun might be requested by officials of the tribe to discipline or even execute wrongdoers. Some Egungun are also known to have used their power to lead entire communities to war. During happier times of celebration, the Egungun most often represent a family’s ancestral lineage. And there is yet another group of Egungun who are professional entertainers. These Egungun “dramatise contemporary events in each community. For examples, they mimic prostitutes, sanitary inspectors, white couples, drunkards, etc” (Babayemi 2). While the people that present themselves as Egungun are always male, they may play the role of either a man or woman. Some Egungun even appear as young children.

The Egungun are known to emerge at almost any time of the day or night, but they are always certain to be present at the annual Egungun festival. These festivals last seven, fourteen, seventeen, or twenty-one days and their date is set by a diviner. During the festival, it is believed that the spirits of the Egungun come down from the heavens to “share physical fellowship with their relatives on earth” (Babayemi 2). Each Egungun is scheduled for a specific appearance, and in the effort to present the most memorable show, there is often a great deal of negotiation on the part of families to secure a date from the cult when the least number of other Egunguns are to appear. “On a day a lineage egúngún comes out, the lineage drummers assemble early in the compound of the lineage head, they start drumming, calling the names and invoking the spirits of the principal men that are deceased in the family” (Babayemi 35). As the time of their appearance draws near, the drummers and the women of the family begin to sing as the music grows louder and louder. When the Egungun finally emerges, their first stop is the graves of the male members of the family. After a short ritual, they move on to the homes of their relatives, where they bless the living and receive gifts of thanks. They then continue on through town, where they stop every so often to display their dancing skills and to bless those who have come to watch.

The organization of the festivals is handled by Egungun cults. Little is known about these “Secret Societies,” since their knowledge is carefully guarded and rarely written down. Most of what is known is passed on through myths and rituals. One such myth explains that the Egungun cults were created as a means for providing stability to the community. The story is that the earth was very unstable and so Olódùmarè sent the Egungun down to help. These heavenly spirits secretly landed in the sacred grove. “They had to disguise themselves to carry the necessary rituals to the four corners of the earth; after that the earth became stable” (Babayemi 10).

The Egungun do indeed provide a certain amount of stability to Yoruba society. They are still to this day called upon as a means of authority to settle local disputes, and their divined knowledge is often consulted in times of trouble. There is also a certain amount of societal control that comes with the belief that the spirits of the Egungun can influence the community from above, especially if they are not happy with the behavior of a family member. This is due to the fact that most Yoruba believe that once a person has made the transition into the After-Life, “they have been released from all the restraints imposed by this earth; thus they are possessors of limitless potentialities which they can exploit for the benefit or the detriment of those who still live on earth. For that reason, it is necessary to keep them in a state of peaceful contentment” (Idowu 207). Every Yoruba lives with the knowledge that they too will one day become an ancestor.

The end of life for an Egungun performer or member of an Egungun cult is handled with great ceremony. The burial and preparation of the body is supervised by other Egungun before the coffin is buried in the floor of their home. Sacrifices are made to mother earth and an elaborate ritual ensues to mark the grave. Before the body is buried, it is put on display for a day or two and may even be taken around town for a final farewell. Singing, dancing and merriment are all part of the proceedings and the entire family is present when the coffin is finally lowered into the grave, as final rites are performed. “A cock or a goat is killed, the blood sprinkled on the coffin, and the head buried with the corpse” (Babayemi 49). Several other rituals usually follow in the days to come to ensure that the deceased spirit finds its way to the ancestral realm.

Life for every Yoruba is a series of changes, yet the Egungun and their rituals continue to survive. Margaret Thomson Drewel points out that: “Unfixed and unstable, Yoruba ritual is more modern than modernism itself” (20). It continues to fluctuate in response to such influences as: marriage, migration, religion, politics, war, economics, and modern technology. Even so, these earthly spirits continue to provide a thread of stability in ever-changing Yoruba society through their continued participation in religious, political and social events. Yet, most significant of all, the Egungun provide a living link to the ancestral legacy of the Yoruba.

Works Cited

Babayemi, S. O. Egungun among the Oyo Yoruba. Ibadan, Nigeria: Oyo State Council for Arts and Culture.

Ọmọ Oòduà Naija Gist | News From Nigeria | Entertainment gist Nigeria|Networking|News.. Visit for Nigeria breaking news , Nigerian Movies , Naija music , Jobs In Nigeria , Naija News , Nollywood, Gist and more

Ọmọ Oòduà Naija Gist | News From Nigeria | Entertainment gist Nigeria|Networking|News.. Visit for Nigeria breaking news , Nigerian Movies , Naija music , Jobs In Nigeria , Naija News , Nollywood, Gist and more

Yoruba people IN VENEZUELA? Venezuela hadn’t a Yoruba tradition till de 70’s when CUBAN oloosa, that aren’t mentioned brought your gods to that country. Venezuela didn’t have Yoruba ancestry. They are of fongbe origin as I’ve herd but they didn’t manage to keep their spiritually live. Is sad seeing how Yoruba people speak about the States & Venezuela just because this where money is! It was Cuba that arise the interest in Yoruba religion that know is providing clients from that and other country to Yoruba priests. Nor in Venezuela or in the US they have got Eegun… you know why? Because in Cuba we just don’t have them (as it happened in Brazil, where they were able to keep this tradition).