“Baba Oyo,” I said one afternoon when I was alone with him, “you are very soft, too gentle, with Iya Oyo. You are not like all the other Baba I know.”

Baba Oyo laughed. “What does too gentle mean?”

“I really don’t know how to say it,” I said. “But you don’t…. When you talk with her…. You don’t argue or order her to do things. You speak softly. It’s as if you have to persuade her kind of. That’s not very manly. That’s not how the other Baba talk to their wives. Is it because you are a pastor?”

Baba Oyo laughed again.

Then he raised his voice, and called, “Iya Oyo. Come, quick. Your son has something to tell you!”

Immediately Iya Oyo appeared. She carried two bowls, one full of okra that she was cutting up into pieces.

The other bowl had water in it, and it contained the okra that she had already cut and placed in the water. The bowl with the water had a small knife she used to cut the okro inside it.

She stood next to the two of us. She expected me to ask her my question. I was scared. I didn’t expect Baba Oyo to call her. It was supposed to just be a male-to-male talk between Baba Oyo and me.

I was silent.

“Go on,” Baba Oyo said, “ask her the question you just asked me.”

“I mean, em, em…” I stammered. “I wasn’t really asking a question.”

“He asked me why I am so soft with you,” Baba Oyo said. “He said I am not like the other Baba in the neighborhood. That I lack the confidence to order you around.”

Iya Oyo sat down next to me. I wanted the ground to open up and swallow me immediately. She heaved a deep sigh.

“You have never heard of Osetura, obviously,” Iya Oyo said.

“How is he expected to hear of Osetura,” Baba Oyo said. “He is not a Babalawo, He is from a Christian home. He attends a Christian school. He is also a Chri—“

Iya Oyo sharply interrupted him, “He is not a Christian. He is too young to decide what he will become. Let me tell you about Osetura.”

Baba Oyo reached for his tobacco pipe.

Iya Oyo continued to cut up the okro into the bowl of water.

“At the dawn of time,” Iya Oyo said, “soon after humans populated the world, everything suddenly turned upside down.”

I looked up into her eyes, and I saw that she was not mad at me, but just wanted to tell me a story, so I relaxed.

“Suddenly,” Iya Oyo continued, “everything changed for the worse. The rain stopped and drought descended on the land. Nothing grew. Women did not get pregnant. Men became infertile. Domestic animals began to fall one by one and were dying.”

“That is Oseture,” Baba Oyo said, in between puffing on his pipe.

Iya Oyo continued. “People decided to send a delegation to Olodumare to ask him what was wrong. They could no longer continue that way. When the delegation got to the abode of Olodumare, they narrated their stories of horror, how things were upside down, and how they were dying because their medicines that once worked no longer were efficacious, and how hungry they were and how the sun was burning up the land and there was no rain.”

“Terrible tale,” Baba Oyo said.

“Then Olodumare asked them one question,” said Iya Oyo. “Where are the women members of this delegation? I want to listen to their side of the story.”

The members of the delegation looked around them. Their leader said, “We did not come with any women. We represent them. Whatever we say is final. We just tell them what to do and they do it. Whatever you tell us, we will deliver the message to them, if they need to know. They probably don’t even need to know, unless there is something we need them to do for us.”

“Listen now, Moyo,” Baba Oyo said. “This is where you get the answer to your questions.”

Iya Oyo continued. “Then Olodumare told them, ‘This is why your world is upside down. You have pushed your women behind and turned them into second-class citizens. Who told you they were your servants to be sent on errands? I made men and women to be equal, but you have created inequality on earth. That is why you have brought problems to yourself. And your problems are just starting unless you change your ways and bring women as equal partners into all your deliberations and activities. Now go back to the world and do accordingly. Things will turn around for good when you change your ways. But if you don’t, your sufferings have just started.”

Baba Oyo said, “Have you gotten the answer to your question now, Moyo.”

I nodded. Iya Oyo got up, saying, “I have finished cutting up the okro. Your lunch will soon be ready.”

She left the two of us.

As I looked at the picture of the politicians of the southwest as they held a meeting recently, I noticed that all the people in the picture were men. They were gathered to solve the chaos that is happening in the country.

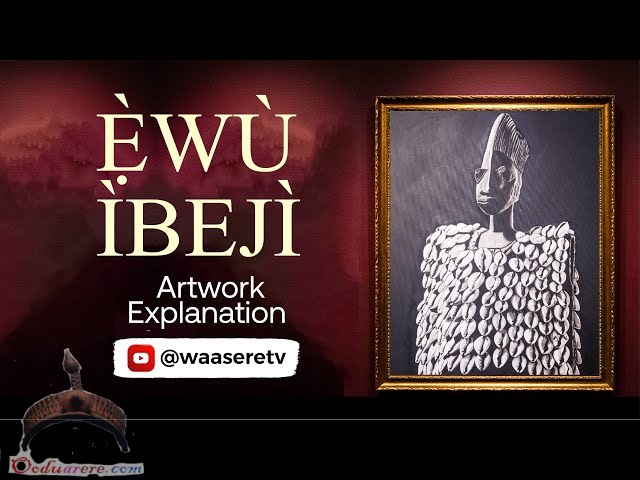

I remember the story of Osetura that Iya Oyo told me as a child. I, therefore, did a drawing of the Odu Osetura, which I later studied in Ifa cosmology, as I grew up.

Could the chaos that we are now experiencing in southwest Nigeria be partly a matter of Osetura, as the photo seems to suggest?

Ọmọ Oòduà Naija Gist | News From Nigeria | Entertainment gist Nigeria|Networking|News.. Visit for Nigeria breaking news , Nigerian Movies , Naija music , Jobs In Nigeria , Naija News , Nollywood, Gist and more

Ọmọ Oòduà Naija Gist | News From Nigeria | Entertainment gist Nigeria|Networking|News.. Visit for Nigeria breaking news , Nigerian Movies , Naija music , Jobs In Nigeria , Naija News , Nollywood, Gist and more