Such a statement was made in light of some Western countries pushing forward the idea of reducing the use of fossil fuels in Africa. At the same time, some African countries are asserting the right to develop their rich gas and oil reserves to combat energy poverty.

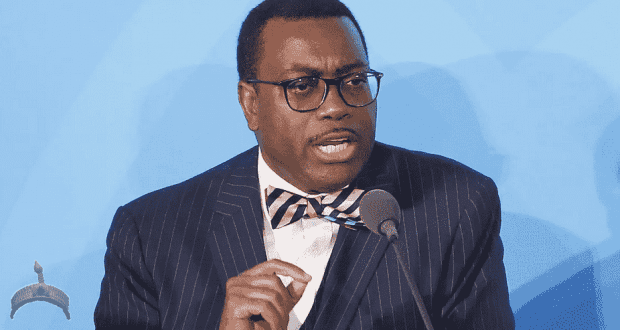

Africa’s right to use its natural gas must be reflected in all the contracts and agreements made during the ongoing COP27 climate summit, argued Akinwumi Adesina, the African Development Bank (AfDB) President.

“Africa must have natural gas to complement its renewable energy,” Adesina pointed out earlier at the same summit venue.

The Minister emphasized that even if Africa triples its natural gas production, its contribution to emissions “would only rise by 0.67%”.

At the same time, he stressed that Africa is also making concrete efforts to increase the share of renewable energy used on the continent. In particular, from 2016-2021, the AfDB invested 85% of its funds in renewable energy. As for now, AfDB is attempting to raise $25 billion through the African Adaptation Acceleration Program, to implement a partial energy transition.

And yet, it’s impossible to fully rely on renewable energy sources only, as they do not always work equally efficiently, Adesina noted.

“We must recognise the special nature of Africa. Africa has the highest level of energy poverty in the world,” he pointed out, underlining that “600 million [African] people today… don’t have access to electricity.”

The Minister also stressed that developed countries actually produce most of the climate-damaging carbon emissions.

“And so Africa, that did not really emit, should not now be penalized for not even being able to use a little bit of gas to complement its natural resources,” he concluded.

Adesina is far from being the first to talk about the importance of gas use for Africa. A few days ago, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni condemned the West for opposing African gas and oil projects, as European countries themselves are continuing to invest in the development of traditional energy sources both on their own territory and on the African continent.

Previously, Sudanese-British billionaire Mo Ibrahim stated that Western countries forbid Africa from developing and utilizing its own gas resources, of which the continent possesses a large amount, approximately “500 trillion cubic feet of gas.”

The CEO of Africa Finance Corporation (AFC), Samaila Zubairu, expressed a similar point of view.

According to him, energy access should be “efficient, reliable, and affordable,” and Africa needs energy access that doesn’t jeopardize African economic development.

The resentment of African leaders is an apparent reaction to the West, making green energy transition one of the main agendas of recent years and widely opposing countries, which are not eager to fully accept the idea.

In September, US climate envoy John Kerry warned against investing in long-term gas projects in Africa, saying that such projects will most likely not pay back their investments, due to plans to reduce the use of gas and switch to alternative energy by 2030. His words echoed similar points made in a previous year’s International Energy Agency report, which stated that investing in African gas projects could threaten the global net-zero goal of 2050.

In late September, the European Parliament summoned a French TotalEnergy representative to justify the company’s participation in the development of the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP), initiated by Uganda and Tanzania. This followed an EU resolution from the same month which accused the EACOP project of “posing environmental risks” and urged it to be halted, prompting a TotalEnergy representative to be called to account.

The resolution was subsequently slammed by Uganda’s government, with Parliament Deputy Speaker Thomas Tayebwa accusing the EU of “economic racism, neo-colonialism, imperialism and double standards.”

Meanwhile, Sub-Saharan Africa is a region that accounts for 75% of all people who lack access to electricity. A recent report by the International Energy Agency (IEA) showed that the number of people, including Africans, who live without power (about 759 million), is expected to grow; according to UN Population data, the worst-affected countries have among the highest birth rates in the world.

Ọmọ Oòduà Naija Gist | News From Nigeria | Entertainment gist Nigeria|Networking|News.. Visit for Nigeria breaking news , Nigerian Movies , Naija music , Jobs In Nigeria , Naija News , Nollywood, Gist and more

Ọmọ Oòduà Naija Gist | News From Nigeria | Entertainment gist Nigeria|Networking|News.. Visit for Nigeria breaking news , Nigerian Movies , Naija music , Jobs In Nigeria , Naija News , Nollywood, Gist and more