“Prof, I have an update for you,” her voice said with urgency.

It’s my “friend,” the one who doesn’t know whether or not to disclose to her daughter in Canada that the man she had always called father is not her biological father.

“So glad to hear from you again,” I said with feigned enthusiasm.

I was done with this matter, truth be told. What more could she have to say?

“Lots of people commented about you on my Facebook post,” I told her. “They all have important suggestions for you.”

“And I read every one of these comments,” she replied. “They were so useful. But I am still confused. What is your opinion?”

“I’m still reading the comments,” I lied. “Hundreds of them. You must be in Canada with your daughter now, guessing from our last discussion.”

“No, prof,” she responded. “My flight was scheduled for last Friday, but it was canceled. We were to make a connection in Houston, but the icy weather condition in Houston made them cancel the flight. We were asked to consult our agency and reschedule.”

“Have you rebooked your flight? So when is your flight coming up?” I asked.

“There is a new development, prof,” she replied. “It’s good that the weather cancelation came up.”

“Why is that?” I asked. “Hope it is a good development.”

“It is good news,” she said. “My daughter is pregnant.” She screamed in delight.

“It is good news indeed,” I agreed. “She will need you, even more, to care for her baby when she gives birth.”

“I am so relieved,” she said. “I had been really worried about her because of the complications she had when was delivered. She was barely seven months in the womb when I delivered her prematurely. She was so tiny. The doctor said she might have medical complications as she grew up.”

“Any complications?” I asked.

“None at first,” she responded. “But as she grew up and other girls her age were giving signs of turning into women, she did not menstruate or show signs of developing breasts. Not even at sixteen. Her father and I were so worried.”

“That’s a natural reaction,” I said. “Did you do anything?”

“Yes, we did,” she responded. “We took her to a gynecologist, who started her out on a treatment with hormones and other things.”

“And she responded?” I asked.

“She did,” she answered. “She began to menstruate after a couple of months, and her body began to change into a fuller and more feminine shape.”

“That must have made you so happy,” I said.

“You cannot imagine the depth of my joy,” she said. “In addition, I did something I didn’t tell her father.”

“And what is that?” I asked, concealing the anxiety in my mind.

“I went to a diviner,” she responded. “A priestess famous for reading Ẹ̀rìndínlógún, the sixteen cowries of Yoruba divination.”

“And what did the diviner say?” Did I ask?

She was quiet for a moment. “Are you there?” I inquired.

“Hmmn,” she responded. “After several hours of consultation, the diviner said the problem was not that my daughter would not give birth, but that there is a mystery in the family about her birth. And that the mystery is better revealed; otherwise, it will affect her later in life.”

“Did you tell the diviner the mystery?” I asked. “She probably was referring to your daughter’s biological father, don’t you think?”

“That’s what I thought, too,” she said. “But she didn’t ask me for any detail. So, I said nothing.”

“You probably did the right thing,” I said.

“That’s what I thought too,” she said.

“Everything has turned out right,” I confirmed. “She is pregnant, finally.”

“I shouted for joy when she broke the news to me,” she said. “I had never told her what the diviner said when she was a child. It was an opportunity to do so. So I told her not to believe all those diviners, superstitions, or any such black magic predictions and curses.’

“They are irredeemably superstitions,” I affirmed. “See, you gave birth to your daughter despite Aríṣe’s curse; and your daughter is pregnant despite the diviner’s prediction.”

“See what I mean, prof?” She exclaimed. “These diviners tell us whatever comes to their heads, and we believe them. Thank God I know better now.”

“So, when are you bound for Canada now?” I asked her.

“Not Canada any longer, prof,” she said. “She is moving to Austin in Texas, where her husband is relocating from Washington, DC, where he lives. He got a job in the tech industry. My daughter says he is an engineer developing software for the medical field. He came to Ontario to give a talk about medicine and the cyber industry, and that’s how they met about a year ago. She relocates to Austin from Ontario, gets an apartment, and her husband moves in to join her from DC.”

“I live in Austin,” I said in excitement. “How coincidental. I will meet you and your entire family when you relocate!”

“Seriously?” she asked. “I thought you lived in Houston! That would be so wonderful to meet you in Austin!”

“It’s a shame that this is the worst time to relocate to Austin,” I warned her. “Housing is so expensive. Everybody is moving to Austin and driving the cost of housing beyond the reach of everybody.”

“My future son-in-law is wealthy,” she said. “Agbeke says his house in Potomac is worth more than one million dollars. Agbeke is not poor by any stretch of the imagination. She earns a fat six-figure salary as an oncology specialist.”

“You are all set, then,” I concluded. “You are in for a great time. I came here without a dollar in my pocket and struggled to make ends meet.”

“I applaud you, prof,” she said. “I have been your admirer since I was a child. But women are not allowed in our Yoruba culture to make the first move, otherwise, I would have asked you to be my boyfriend.” She chuckled nervously.

“I’m hoping that women are getting braver these days,” I said, also with a nervous chuckle.

“My daughter is certainly braver than me,” she said. “She told me she made the first move on her boyfriend. She said she had never done that before, but some irresistible spirit compelled her to make a move, and she did.”

“That’s love at first sight,” I added.

“That’s what I had for you, prof,” she said. “You probably didn’t notice that poor girl who couldn’t take her eyes off you when you came to buy akírá from my grandmother.”

“Really!” I cried. “You are omo iya alakira! The shy little girl that wore panties and sat in the background when I came to Ile Latale to buy akírá?”

“We always wondered what you did with the akira,” she said. “You were not regular. You came only occasionally.”

“It was when my grandmother visited from Oyo,” I explained. “She was the one who wanted akira and sent me on those errands.”

“I always added a lot of extra when I had the opportunity to package it for you,” she said with a grin.

“My grandmother, Iya Oyo, always remarked that the akira was cheap beyond generous,” I said.

“That was because I had a crush on you,” she said.

“And what is your name?” I asked.

“Aduke,” she said. “It is unbelievable that you are in Austin. It means I already have a friend waiting for me in Austin,” she continued. “This journey is going to get really exciting.”

“Sounds like an adventure,” I said.

“May I ask, prof?” she said. “Just so I know: are you married, dating anyone seriously, or romantically involved in a deep way with a woman? So I know what to expect?”

“It’s complicated,” I told her.

“Good answer,” she said. “Prof, there’s a lot you don’t know about me. May I tell you a bit more about me?”

“I’m listening,” I said.

To be continued.

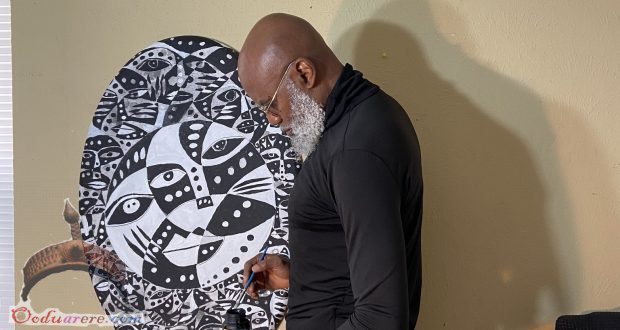

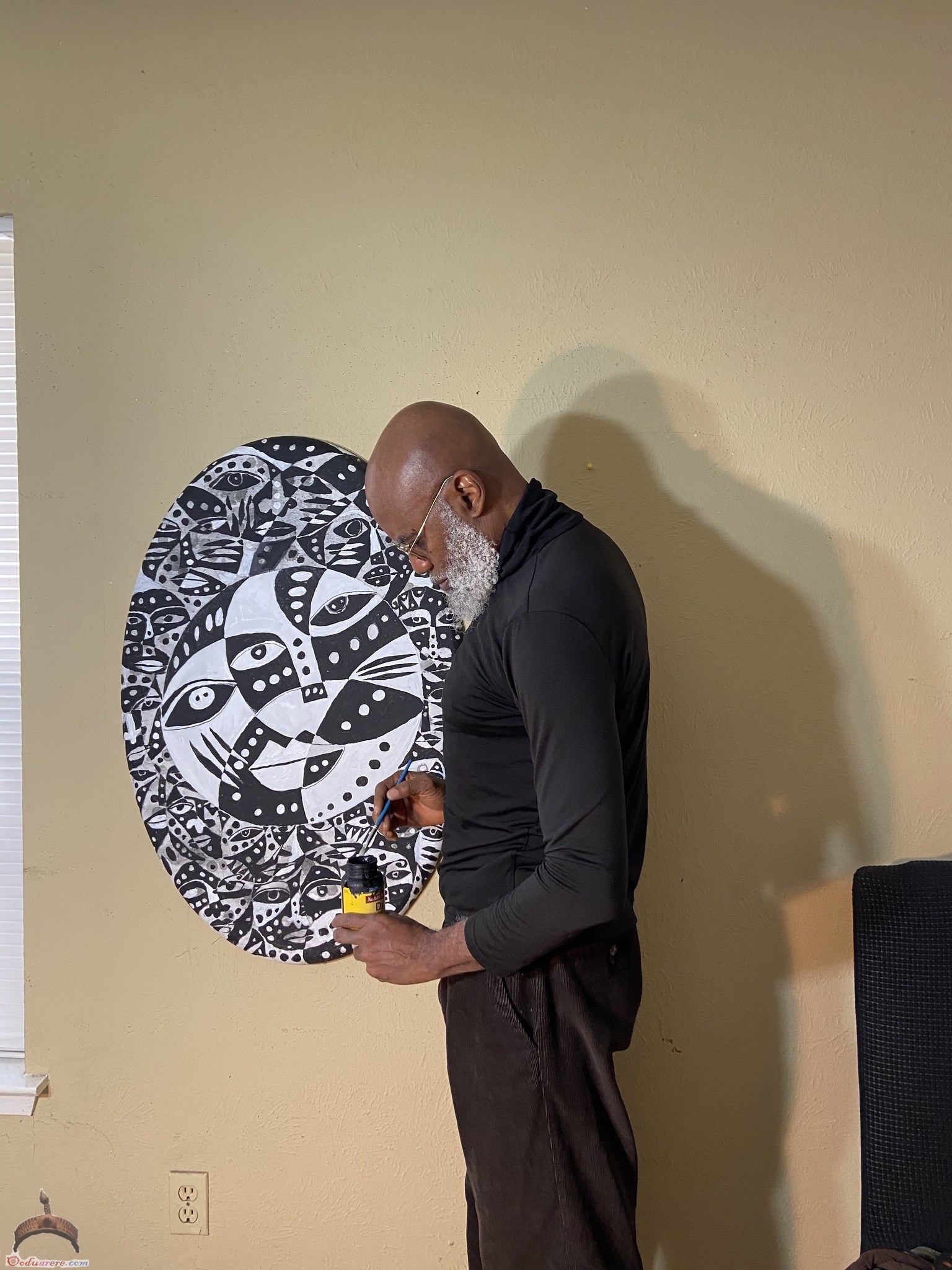

Last week, we had NEPA in Austin.

After the deep freeze, lots of trees went down and they cut electricity for two days.

It meant no heat.

But I had water and gas and lots of time.

So I started to paint, and paint, and paint.

By Prof. Moyo Okediji

And OJU LORO WA is one of the products of the Deep Freeze With NEPA.

– Original painter: Prof. Moyo Okediji

Ọmọ Oòduà Naija Gist | News From Nigeria | Entertainment gist Nigeria|Networking|News.. Visit for Nigeria breaking news , Nigerian Movies , Naija music , Jobs In Nigeria , Naija News , Nollywood, Gist and more

Ọmọ Oòduà Naija Gist | News From Nigeria | Entertainment gist Nigeria|Networking|News.. Visit for Nigeria breaking news , Nigerian Movies , Naija music , Jobs In Nigeria , Naija News , Nollywood, Gist and more