At first, she just leaned her head against mine.

But later, she decided to recline and placed her head on my lap.

“Hey, tell me if I’m making you uncomfortable,” she said.

I was in heaven all the way to Port Harcourt, with Hilda keeping my body warm.

At first, I was quite concerned about where I kept my hands because I didn’t want to give the impression that I was taking advantage of her proximity to me.

I still wanted to maintain some distance, however symbolic.

But later we became so comfortable with one another that it no longer mattered where my body stopped and hers began.

My mind drifted to Gina. It was as if Hilda could read my thoughts.

“Who was that pregnant woman who came to see you on the night we arrived from Ife?” Hilda asked, suddenly.

“Pregnant woman,” I asked her. “Oh, Gina! You could tell she was pregnant?”

“Yes. It was not so much her stomach,” Hilda said. “It was her body language.”

“But you only saw her briefly,” I said.

“It was enough to tell,” she replied. “You didn’t know?”

“Oh, I knew,” I responded.

“Your pregnancy?” she asked.

“Oh, no,” I said quickly. “Not mine. My friend’s.”

“She has not returned since that night.”

“No, she hasn’t,” I said. “She traveled out of town.” I lied.

“I see.” She said nothing anymore, heaved a sigh, and soon fell asleep, her head on my lap.

We stopped at three places only, to refuel, use the bathroom, and get some food for the road.

It was such a quiet trip, with Rufus driving and Obaseki seated next to him, passing food and drinks to him when asked. Obaseki hardly said anything beyond, repeating “I like this journey. Thank you, Mr. Rufus.” Or, “I cannot believe I’m having this experience. God bless you, Mr. Rufus.” He did not stutter.

Akatakpo slept most of the way after drinking a beer. He hardly ate anything. He woke up to open a beer, drink it, and go back to sleep.

Finally, we touched down, and professor Ola Rotimi was waiting for us at the theater, though we arrived late. He took us to his house where we spent the night.

The following day, we worked on setting up the stage and did a quick rehearsal.

The day after, we did the show.

The performance at the University of Port Harcourt was the first stage show by the students of the University of Benin.

But Rufus had worked so hard with them that they looked like seasoned performers on stage.

Mofe Damijo played his role so splendidly as Kurunmi, and everybody at that university hall knew instantly that a star was born.

It was as if he had been acting for decades, though that was his first appearance on stage.

After the performance, Professor Ola Rotimi took all of us to a banquet.

He gave a speech. His greatest joy, he said, was to see his former students go better than him.

“In his directing of my play,” Ola Rotimi said, “Rufus has introduced many great ideas that did not occur to me when I was writing ‘Kurunmi’.”

He expressed his delight about the high standard of the performance and said nice things about the potentials of the actors.

Rufus thanked everybody.

At about twelve midnight, Rufus told the cast and crew that they should stay overnight.

But that we in the bus were returning to Benin that night, just the way we drove to Port Harcourt.

“You are ready to drive back, Mr. Rufus,” Obaseki asked him. Rufus nodded and we piled into the bus.

Seated next to Rufus, Obaseki couldn’t stop praising the performance and the hard work that Rufus did to make it a success. He did not stutter. He was really calm. He spoke lucidly and clearly. It was as if Obaseki was a totally different person.

“The last performance of this caliber that I witnessed was by also Ola Rotimi, at the Cultural Center in Benin,” Obaseki said. “The play, titled Ovenramwen Nogbaisi was about the British sack of the Benin kingdom in 1897.”

Rufus said, “What a play! Rotimi is such a great director too.”

“Absolutely! What a play!,” Obaseki agreed. “I had just returned from Hungary. In fact, I was deported. It’s a long story. But I went to a small museum in Debrecen. I just wanted to get out of my apartment because I was feeling very depressed. The doctor was giving me some medications that made me sleepy and I hated them. He also suggested that I should go out more. But it was so cold. Anyway, one Saturday, I went to this museum just to get out. To my surprise, what did I see inside a glass cage in the museum? It has the head of our Benin Oba. It said, in Edo, “Obaseki, rescue me from this cage.” I did not hesitate. I immediately opened the cage. But they arrested me, brutalized me and deported me after a sham of a court hearing.”

“You are not supposed to touch an object in a museum display, Obaseki,” Steve said.

“Yes, you are,” Hilda said. I thought she was asleep. “If the object spoke to you in your native language and begged to be rescued!”

Obaseki continued talking. “I arrived Benin from Hungary broke, depressed and angry. Then, one evening, Joshua said we should go to the Cultural Center to watch a play by Ola Rotimi. I will never forget that evening. Jimi Solanke acted the part of the tragic king. It was so real, they had to cancel the play after the second run. It was supposed to run at the Cultural Center for a month. But when the people of Benin saw the play, they became angry and wanted to start attacking the white people in the city. You should have seen Jimi Solanke as the tragic king, after losing the war, captured and in chain. Everybody in the audience began to cry. At some point, people were shouting and yelling for revenge.”

“The same Jimi who came with us from Ife?” Hilda asked. “I would have loved to see that.”

Obaseki continued. “I believe the spirit of the ancient king entered Jimi Solanke’s spirit that night. Though he was speaking in English, many people in the audience swore that what they were hearing him speak on the stage was the Edo language. But Jimi Solanke does not speak Edo. He was speaking in English. Olodumare! The night was definitely magical. It sounded to me like he was speaking in Edo too.”

Obaseki paused. He brought out his smoking kit from his bag. I thought he was going to roll some marijuana. But no, it was just tobacco leaves. He continued speaking as he rolled the cigarette.

“That was the night I met Dr. Jude, the Englishman who is a doctor here in Benin,” Obaseki said. “The news of the play was all over television and radio. Those who did not know the history of the British and the Edo were learning what happened for the first time. A mob had gathered to burn Jude’s hospital after the news of the play had spread around. I joined the mob. I was very angry with what I saw in the play and did not hesitate to join the job. You know the disgusting thing? Nigerian policemen were firing at us, to protect him and his property. They killed three people in front of that hospital. Nobody said anything. The press did not even report the killing. The police said they saved the hospital from being destroyed.”

Obaseki finished making his cigarette and lit it. He inhaled deep.

“How could your own police be killing you for the protection of foreigners?” Obaseki asked. “It’s abnormal, the way my people think.”

He continued smoking. We didn’t say anything.

“Hey, Obaseki,” Steve said, “don’t be so selfish. You don’t want to share? Pass the smoke back here, will you?”

“There,” Obaseki said, passing the cigarette to Steve. “I couldn’t get over it, that massacre by the police. One day, I got up early in the morning to look for Dr. Jude and kill him. I dressed up in a red shirt and black pants, and went to buy a knife before setting forth on foot to his clinic.

You can imagine me walking all the way from the Oba palace to the Oluku junction. That’s probably ten miles, maybe more. In the blazing hot sun. I just kept moving, kept going. My entire attention was focused on what I wanted to do. I didn’t want to think about it, so that my mind would not change. I kept walking, straight ahead, not looking at anybody, or speaking to anyone. Rain began to fall, but I kept going. It was a heavy storm, and the wind was blowing really hard, but I did not stop. At some point, I didn’t know where I was again. By the time I regained consciousness, I was in a local mental hospital, tied to a huge log. They flogged me daily, mercilessly, and gave me some sickening things to drink.”

We sat quietly, hearing only the humming sound of the Mitsubishi bus traveling through the night, as we listened to him. We were now beyond the city of Owerri and the darkness of the outside world enveloped up in the bus.

The sky was dark, but millions of stars twinkled as the bus kept moving. Occasionally, there were some fleeting lights, as we passed by some villages a little removed from the side of the road.

Obaseki kept talking.

“For how long I was tied down there to this heavy log, I don’t know. But they kept flogging me daily and kept telling me they were not going to release me until I was able to physically move that heavy log. You cannot believe how huge and heavy this log was. I didn’t think it was possible to move it. But they kept beating me and giving me this wretched thing to drink daily and I knew they were not releasing me if I didn’t move the impossible log. I lost hope after some while. But there was nothing else to do with time, except to keep trying to move this log tied to my waist and hands. I must have been tied there six months, seven, eight, nine, I could not say. One night, after they flogged me for hours, I tried all my best to move this log, but it would not budge.

I screamed with all my throat and kept trying, pushing and pulling and dragging as much as I could, using my mind to will my body to move the log. But it did not move. I kept trying, sweating and weeping, all totally naked, wrestling with this log. Then all of a sudden, I heard a tiny sound. The log moved. Then I pushed again, And the log moved again. All through the night, I kept trying. And by the time they came to flog me in the morning, I was already outside the cell, in the courtyard of the hospital. I had moved the heavy log out of the dark cell. But I was spent and fell on the ground, waiting to be flogged. They stopped flogging me as from that morning. But they still gave me the wretched drink and didn’t untie me from the log….”

Then he rested his head on his arms and started sobbing.

We didn’t say a word. I didn’t know what to say.

“One—one—one—day, when—when—when—when they arrived, I had bro—bro—bro-ken-broken the chain,” Obaseki said, sobbing. His body was shaking.

Then he closed his eyes, and calmed down. Slowly, meditatively, he rolled another cigarette, taking his time to get it perfectly right. He lit it, inhaled deep, and continued speaking again, calmly, word by word:

“They shaved my head and bathed me. The water felt so good as it touched my skin. Cold water first. Then hot water, and cold water finally. Heavenly. And for the first time in God knows how long, they allowed me to walk and pace the short yard. After several days of doing this pacing in the yard, I was allowed to pace the street, from one corner to another. Then one day, they sent me on an errand to the market to buy a tuber of yam, with one of them following me. Then they regularly sent me on errands all by myself. And one day, they said my mother could visit. And after a couple of weeks, they allowed her to take me home.”

Hilda said, “What a story!” I thought she was asleep, her head still on my lap. I stroked her hair gently and she made some sounds of contentment and held my hand.

It went quiet inside the bus. Only the sound of the humming bus was audible as we traveled toward Benin.

“Oga Rufus,” Obaseki said, “you are going too slow. We are hardly doing 50 kph on this wide highway.”

“Excuse me please,” Papa Ru apologized. “Your story carried me away.”

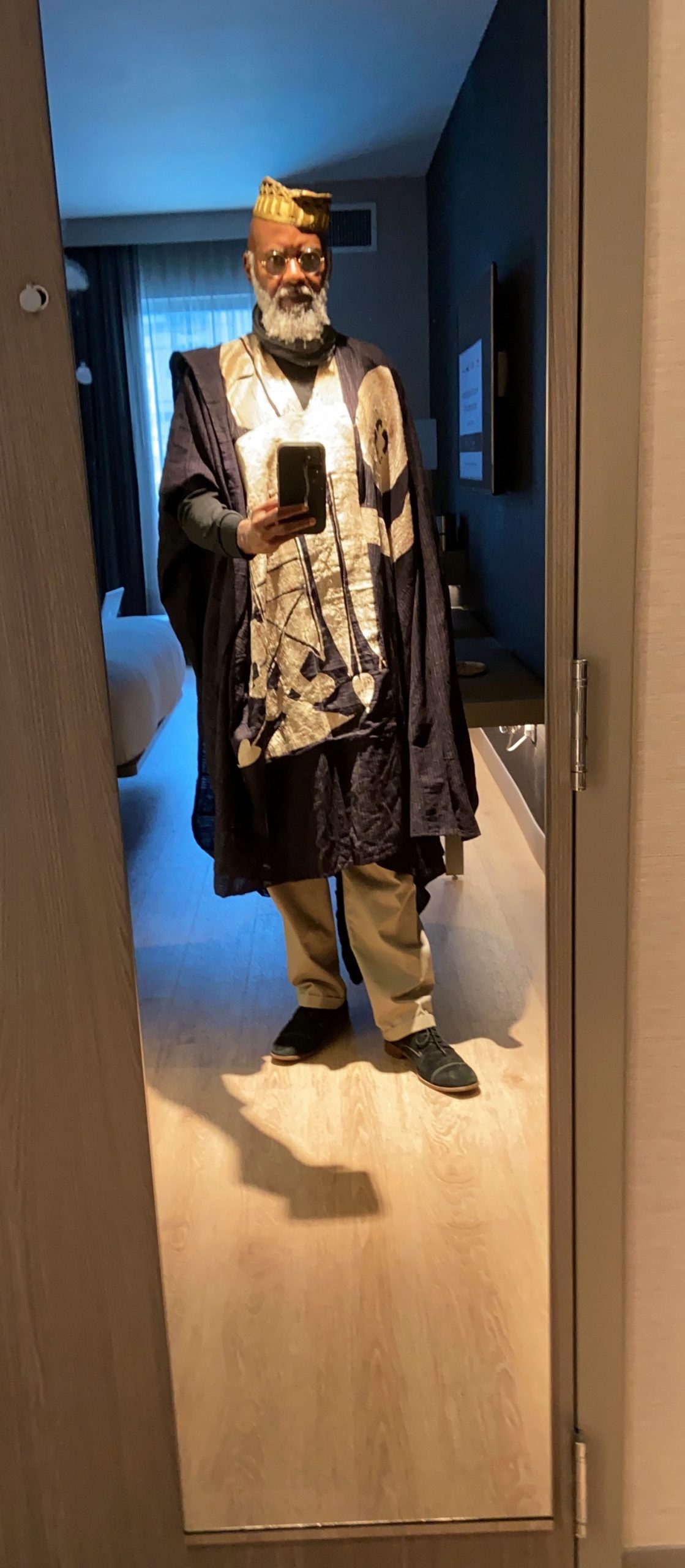

The picture shows me in Atlanta today.

I’m in Atlanta to give a talk at an exhibition featuring the work of six artists.

The first time I am getting out of my house after the outbreak of Covid 19. That was fifteen months ago.

“Yes, me friends, they set me loose again,” as Bob Marley puts it.

Ọmọ Oòduà Naija Gist | News From Nigeria | Entertainment gist Nigeria|Networking|News.. Visit for Nigeria breaking news , Nigerian Movies , Naija music , Jobs In Nigeria , Naija News , Nollywood, Gist and more

Ọmọ Oòduà Naija Gist | News From Nigeria | Entertainment gist Nigeria|Networking|News.. Visit for Nigeria breaking news , Nigerian Movies , Naija music , Jobs In Nigeria , Naija News , Nollywood, Gist and more