“I remember so very clearly when hooligans came to burn down your mother’s shop,” Aduke said. “It’s one of the most vivid memories that I carry from my childhood. I had seen you in school that same day, I think. I’m not sure of the exact date any longer.”

“That fateful day is also vivid in my mind,” I replied.

“You looked so confused and helpless that day,” she said. “I was crying when I saw the look on your face and the other members of your family.”

“Interesting,” I said. “I had no idea anybody was watching us. It was in the afternoon. Most likely in 1963.”

A large crowd gathered in front of my mother’s shop that afternoon as I returned home from school.

I was hungry. The connection between my family and the crowd gathered in front of our shop was unclear to me at that time.

But as soon as I arrived, one of the hoodlums strutting around the front of the crowd sighted me and said, “Here’s one of the children.”

“Push him into the shop and we burn everything down with the entire family,” said the one who appeared to lead the group.

They pushed me into the shop. My mother, who was pregnant, I believe, was seated there, together with my father, looking worried.

It was so unusual to find my father at my mother’s shop at such a time of the day. Normally he would be at home, working on his novel, play, poetry, or whatever he was writing at the moment.

The routine was that at about 7 am, he dropped my mother and the rest of us off at his mother’s shop, and he returned home to work on his writing. He would return at 7 pm to take us back home.

Occasionally, he was at the shop during the day with a couple of friends to drink beer or palmwine, or just see what was going on.

Given the heated political situation at that time, he probably came to see what was going on and found the crisis that was developing.

Operation Wẹtiẹ̀ had already erupted throughout the western part of Nigeria, following the breakdown of law and order in the House of Legislation at Ibadan.

The crisis came emerged from the political disagreement in 1962 between the leader of the Action Group, Obafemi Awolowo, and the Deputy Leader, Samuel Ladoke Akintola.

Awolowo wanted a consolidation of power within the West, while Akintola favored more alliances with the North, where he felt he had more sympathy.

At that point, Akintola was also the Premier of the Western Region. Akintola was relieved of his position as the Deputy Leader of the Action Group in a party convention held in 1962.

The next step was to have Akintola removed by the Governor of the Western Region, Oba Adesoji Aderemi.

But Akintola was smarter. Using his position as the Premier and citing legal authorities, Akintola quickly had the Governor removed before the Governor could remove him as Premier.

The House of legislation on Ibadan became a place of open brawling, throwing of chairs, tables, and anything that was not nailed to the floor by members of the house as they fought to take sides between Awolowo and Akintola.

Members of the public were also taking sides. The Western Region was divided between the supporters of Awolowo and those of Akintola.

Thugs, hoodlums and hooligans were raised by each party to harass the opponents of the other party.

The court system was coopted into the struggles.

There was the case of one of my mother’s landlords who was known as an Akintola supporter in Ile Ife, a city apparently more favorable toward the Awolowo group.

My mom had three shops at that time, and one of the smaller shops had a landlord who was politically active.

He was stunned when court officials and the police came to his house one day to arrest him for escaping from prison.

The situation was that someone pretending to be him had pleaded guilty to charges of battery, assault and robbery at a local magistrate court, without his knowledge.

The person who had pleaded guilty in his name was sentenced to a prison term. That unknown person has led away to prison but was allowed to leave by the prison authorities.

The law enforcement officers therefore came and arrested him for escaping from prison.

I remember the day they came to arrest him, with a police Land Rover Jeep. The law enforcement officers were still trying to enter his premises when word reached him that the police had come to take him away.

What the police didn’t realize was that he had planned for exactly such a situation: he had an escape route at the back.

I was just about 5 years old then, as I watched our landlord descend the top of the building with a secret ladder, land on top of the roof of a nearby building, and before the law enforcement officers realized what was going on, he had disappeared into the large Agboole behind the shop, narrowly escaping capture.

Later, thugs came to his house to destroy the building and loot his properties.

But by the time they came to burn down my mother’s shop, the political situation had deteriorated much further, as the houses of some political leaders in Ile Ife were getting burned.

It was in that context that the large crowd gathered in front of my mother’s shop, and I was pushed into the shop so that they could burn down the shop with the entire members of my family.

As I was just about 7 years old, I didn’t know the full details, but as I sat together with my mother, father and some other relatives in the shop, waiting for them to burn us down, I knew we were in real trouble.

Aduke said, “As I watched you and the members of your family that day, I was praying for a miracle to happen. But I was not expecting any miracle, because the thugs were coming from another operation where they had burned down the house, with the owner, said to be in the wrong political party, narrowly escaping with his life into the bush, while they caught and killed his wife and one of his children. I thought it was over for you.”

To be continued.

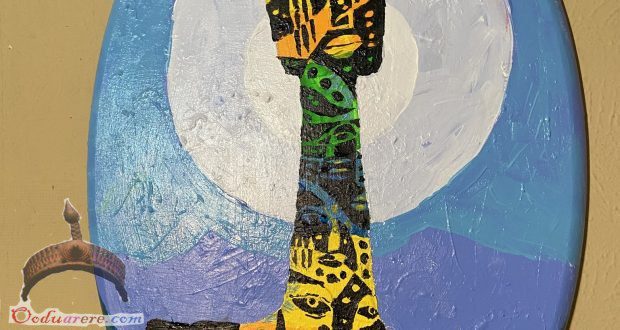

The painting shows Ojú Iná, one of the street thugs who burned down and killed political opponents.

If you take a careful look you will find the disgruntled members of the community depicted on his body.

Ọmọ Oòduà Naija Gist | News From Nigeria | Entertainment gist Nigeria|Networking|News.. Visit for Nigeria breaking news , Nigerian Movies , Naija music , Jobs In Nigeria , Naija News , Nollywood, Gist and more

Ọmọ Oòduà Naija Gist | News From Nigeria | Entertainment gist Nigeria|Networking|News.. Visit for Nigeria breaking news , Nigerian Movies , Naija music , Jobs In Nigeria , Naija News , Nollywood, Gist and more